When I retired as a councillor last May, I contacted Fergus Garrett, the Head Gardener and Chief Executive at Great Dixter to ask if I could work there for a day a week as a volunteer. I knew Fergus, albeit not that well, from my work as Hastings Council leader. He told me to just turn up the following Tuesday. When I did, no-one had any idea that I was expected, but when I said Fergus had told me to come, they sighed and gave me a form to fill in. And so my career as a Dixter gardening volunteer began. It’s been at times wet, cold, tedious, repetitive, hard, and tiring. But it’s been hugely enjoyable. Here’s an account of the Dixter way of the world, how the place runs, and what I’ve learned.

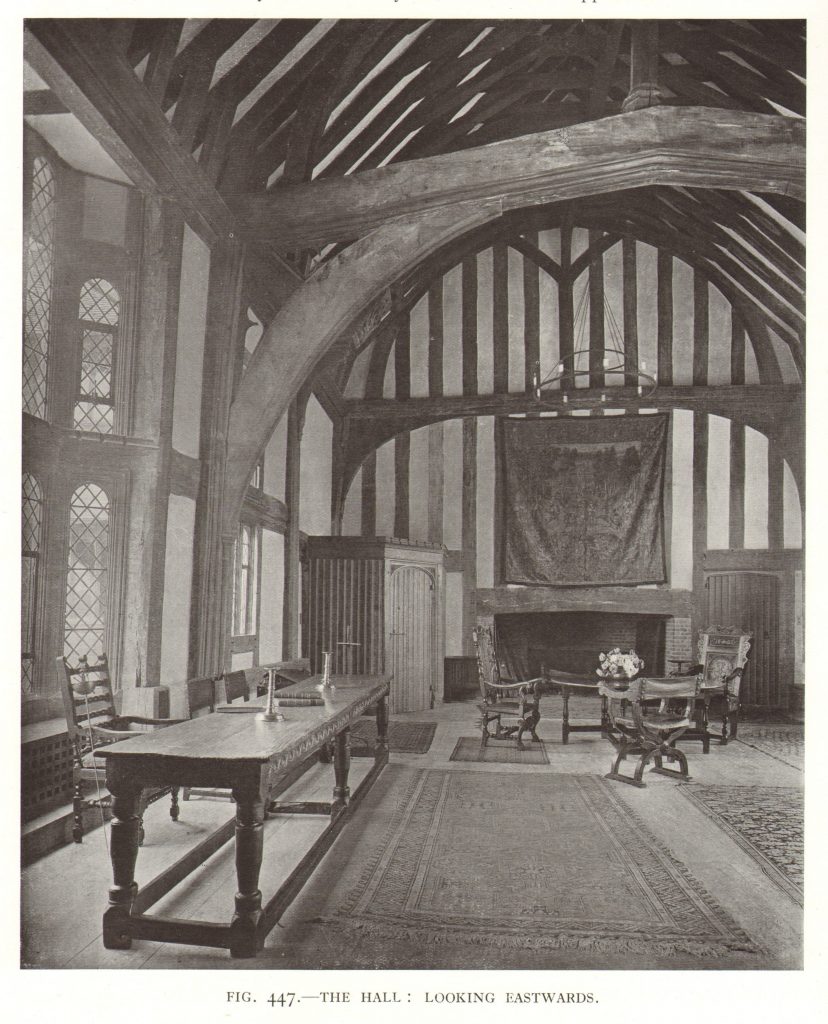

Great Dixter is an estate in the village of Northiam, East Sussex. Great Dixter house, or houses as there are three of them, was a creation of the Lloyd family, who purchased a derelict mediaeval hall-style manor house in 1910 for £75. Nathaniel Lloyd employed architect Edwin Lutyens to restore the manor house and incorporate it into a new house and garden. The house was to be in keeping with the mediaeval theme of the manor house as well as the surrounding vernacular architecture. Although Lutyens designed and laid out gardens around the house, incorporating the contemporary Arts and Crafts style that is evident in the design and architecture of the house, he was not a garden designer. On other projects, he worked with Gertrude Jekyll as a garden designer, but there’s no evidence of her being involved at Great Dixter. What made the design and development of the gardens at Great Dixter special was the lifelong involvement and dedication of Nathaniel’s son Christopher, who made Great Dixter garden what it is today. Christopher Lloyd, or ‘Christo’ as he was affectionately known, developed the garden in an unusual style: much less formal than other gardens of the day, but with an almost unparalleled exuberance, achieved through spectacular displays of ever-changing seasonal colour. Fergus Garrett was Christo’s deputy for many years, becoming Head Gardener when Christo died in 2006. Christo left his share of the estate to a charitable trust, which was eventually able to raise the funds to acquire all of it. The legacy of Christo, and the work of Fergus and his team since Christo died, have established Great Dixter as one of the foremost and most notable gardens in the world, thrusting Fergus into that small elite of international horticultural celebrities, deservedly so.

There are several teams of workers, students and volunteers at Dixter. These include a team that looks after the house, an educational and administrative team, the nursery team, a team that looks after the vegetable garden and wider estate, and of course the ornamental garden team, where I volunteer one day a week, as part of ‘Team Tuesday’. The work in the Dixter ornamental garden is carried out by just four paid gardeners, including Fergus and his deputy Coralie. There is however an array of other, mostly professional, gardeners on educational sabbaticals, bursaries and scholarships, as well as the volunteers. On a normal Tuesday, there are around a dozen of us working in the ornamental garden. What has been so uplifting is that the students there are so young. Not surprising I suppose, students usually are. I was one once. But we so often think about horticulture and gardening as something middle aged and old people do.

To work amongst gardeners who are far younger than me but know ten times as much as I do about horticulture, with my fifty years’ amateur experience, was at first disconcerting. I’d just finished 15 years of sitting in an office telling everyone else what to do. To be given instructions at all, let alone by someone a third my age, took some getting used to. That was emphasised on one particular day, when an incredibly bright and knowledgeable 24 year-old student was telling me what to do. Thanks to a laundry timing miscalculation I’d had to burrow into the back of my drawer to find a pair of underpants that I never wear, and had been there for over 25 years. I really was wearing underpants that were older than he was.

When I started at Dixter, I was hoping to learn all their secrets. And I have done. The secret is that there aren’t any secrets. It’s just a lot of hard work coupled with the trained eye and encyclopaedic knowledge of Fergus and the other professional gardeners. But there are rules that apply, and can be used by anyone in the development of their own garden. The first thing to note about Dixter is that it’s not organic – not quite. The only aspect in which they’re not organic is in the recipe for their seed and propagation compost mix, where non-organic fertilizers are used. What’s in it? OK, that one is a secret, which I could not possibly reveal …

Everywhere else in the garden, the practice is organic. No peat is used anywhere, including in the potting compost mixes, nor are any pesticides or herbicides used, not even chemicals such as pyrethrin that are permitted in organic farming. Nor are any non-organic fertilizers used on the soil. Indeed, much to my surprise when I started working there, no fertilizers are used at all, and haven’t been for many years. As Dixter has a clay-based soil, it retains sufficient nutrients without the need for fertilizers. A light mulch of composted bark is carefully sprinkled onto the soil surface in winter in some areas, and we sometimes add a dash of mushroom compost when planting out, but that’s about it. So why do plants at Dixter always grow to at least twice the size that they do in my garden? It’s all in the soil structure. The soil at Dixter has been lovingly cultivated and nurtured for over a hundred years. It feels and smells so good that it makes you want to roll naked in it, although this temptation for visitors is largely precluded by very dense planting. It’s this soil, rich in natural nutrients free from any additional fertilization, and with a healthy, well-developed microbiome, that makes the plants grow so huge and healthy. Indeed, it can be overwhelming to some, the overall effect can make you feel child-like: are these plants really big, or have I shrunk?

And of course, they compost all the waste material from the garden on site. Which makes for some very big compost heaps. Composting at Dixter is, at first sight, relatively unsophisticated. Everything is piled up into a huge stack the size of a small bungalow and left for a few years. The finished compost is then dug out. It’s true that you could speed the process along by mechanically turning the compost to get the air into it, but just leaving it to do its thing undisturbed works too, as long as there’s a good mix of material and the structure is sufficiently open to let the oxygen in and doesn’t trigger weird anaerobic bacteria to produce all sorts of undesirable chemicals. As a microbiologist, I fuss about compost a lot in my garden. I shred it, I turn it, I’m careful about what I add to it and in what proportions. But you need to be more careful with small compost heaps, which are effectively ‘cold composting’ (although even a small heap heats up quite a bit if it’s working well). A really big, well-oxygenated heap can generate much higher temperatures, taking it into the ‘hot composting’ bracket. This is a faster, fungi-driven, more brutal process. It’s more effective and usually quicker. What they do at Dixter is probably a sort of warm composting, but it works. The compost they produce is mostly used in the vegetable gardens. I’ve not seen any used in the ornamental garden.

Sowing seeds, or taking cuttings, at the right time is important too. I quickly realised that I’d been getting this wrong for years, sowing in spring, rather than getting hardy annuals sown in autumn so they can germinate then, and take off when the weather starts to warm in spring, benefitting from a period of ‘cold layering’. I’ve invested in a cold frame now to help with this, and for the first time have some respectable larkspur and cornflowers, amongst other things, ready to plant out now. But at Dixter, the timing of sowing and ‘bringing on’ is crucial. It’s essential for one of the things Dixter is famous for: successional planting. Put simply, this means making sure that as the flowering period of one plant comes to an end, there’s something else coming into flower to replace it. That’s difficult to achieve, and requires a lot of work, removing or cutting back plants that have finished flowering so they can be replaced, either by emerging perennials that haven’t flowered yet, or by planting potted annuals that are about to flower. This requires a lot of planning, making sure the annuals are at the right part of their growth cycle to replace other plants that have gone over. To do it on the scale they achieve at Dixter requires enormous skill and knowledge of the garden, its soil and its conditions, as well as the changing climate.

Bulbs are an important part of this, predominantly forming the early stages of this succession. Each autumn, the Dixter garden team plants thousands of new bulbs, to replace and extend the existing ones. These spring bulbs are a succession in themselves, starting with the snowdrops, followed by crocuses, narcissi, and tulips. Like everything else at Dixter, planting densities are much higher than would be advised on seed or bulb packets. When planting narcissi in pots for example, we pack them in tight, as many as will physically fit, in some cases even planting them in a double layer. Visitors often ask how we achieve the magnificent spring pot displays. The answer is simple: put more bulbs in.

For the shrubs, pruning is important. More important than I’d realised, it made me notice how neglected and sadly underperforming most of the shrubs in my garden were. There are general and specific rules here. The general rule is that early flowering shrubs are cut back immediately after they’ve flowered. Later flowering ones are pruned in winter. With more congested or overgrown shrubs that need reinvigorating, take out a third of the total growth each year. But don’t just snip a third of the length off all the branches … take out weak and crossing branches, open up the structure, give it space to breathe. However, a few shrubs have different, specific requirements. Buddleias, for example, appreciate being cut down virtually to the ground each year at the end of the winter, as they grow so vigorously and flower on new growth.

Most gardeners seem to fret the most about pruning roses. What I’ve learned at Dixter is that, for the shrub roses and hybrid tea roses you’ll find in your garden, you can prune them pretty much how you want. It’s good to have a nice, open structure, a pleasing shape, no crossing, dead or diseased branches. But for some of the Dixter roses, they do it a different way, encouraging a few uprights to grow long. When these flower, the weight of the blooms makes them curve down in a floral arm animated by the wind. Of course, this is best done for roses away from paths, where a breeze can fling a thorny rose whip across someone’s face. But it can be a wonderful effect. As ever, there are exceptions. Dog roses, the wild native roses, always flower at the ends of last year’s growth. So if you cut them back at the end of each year, they won’t flower – which explains what had happened to my sad and tangled monstrosity. Rugosa roses, by contrast, perform best if they’re cut right down to the ground each year, maybe leaving a couple of the stronger stems just a few centimetres long. In spring, people come to Dixter from literally all over the world, although mostly America, to learn how to prune, on special pruning courses. It’s that important, both for their gardens, and for Dixter’s finances.

I have been asked by people who know I volunteer at Dixter when we ‘finish for the winter’. We don’t. Winter is, if anything, the busiest time. The earth might well be as hard as iron, although not often these days, but there’s plenty to do. As well as propagation, there’s clearing away all last year’s growth for all the annuals, as well as perennials that die back to the ground in winter. There’s a lot of weeding to do too, getting out all the perennial weeds. Some parts of the garden had become infested with bindweed. The only way to get rid of it was to remove all the plants and dig out the roots, then replace the plants. That’s a time-consuming job, not to mention tiring. Some of the older, well-established plants can get a bit overwhelming, and have to be brought down to size. Jodie, one of the other Team Tuesday volunteers, and I spent an entire, muddy, exhausting day tackling an enormous persicaria. It put up a brave fight, but we defeated it in the end, pulling roots out of the cold ground like they were leathery snakes burrowing into the underworld. It will be back of course, in a couple of years. Perennial plants don’t necessarily have long lives. Many of our native trees have lifespans less than we humans. But I’m guessing that persicaria will outlive me.

And then, as winter turns the corner and spring arrives, everything changes. Bulb growth pushes up from the ground. Blossom bursts onto the branches of trees. Colour starts to replace the winter greys, we start breeding lilacs out of the dead land. And, strangest of all, people appear. After a winter of it being just us and the garden, the still quiet of it, suddenly there are visitors all over the place. It feels odd, like they shouldn’t be there, intruding on this pristine place. You have to cope with them, you have to make sure you don’t leave tools all over the paths, you have to be tidy and, most importantly, you have to be nice to them.

The visitors are, of course, what the garden is for. It’s for people to enjoy, to learn, to love. But they can be difficult. Most are friendly, polite, and considerate. But a few aren’t, and get quite huffy and rude if you can’t answer their questions. Some expect you to know the names of every plant in the garden, which is tricky for a day-a-week volunteer, particularly one like me who doesn’t have any horticultural training. I only really know the names of plants I’ve grown myself. The professional gardeners know most of them, but I suspect only Fergus knows every single one.

Some of the questions we get asked are a little odd. I get asked a lot about the history of the house, which is at least easy to learn. The commonest questions I’ve been asked are probably: where’s the café? Is the garden organic? Why are there so many weeds? If I left my garden to just go wild, would it look like this? And is the cat around? ’The cat’ is called Neil, although is actually female. She was brought to the garden as a stray kitten from Afghanistan, by Fergus’s brother who was working there. If you visit Dixter and see a group of people clustered round one spot photographing something, it’s not an especially rare plant; it’s Neil. Some of the questions can be quite insulting. One visitor recently asked one of the professional gardeners whether they were a ‘proper gardener’ or ‘just a weeder’.

Ah yes, weeding … there are no ‘weeders’ at Great Dixter. Indeed, all the practical gardening tasks are undertaken by everyone: volunteers, students and professional gardeners. Even Fergus will happily join in with a bit of weeding, when he’s not in meetings, on international lecture tours, or appearing on telly. Indeed, he’d much rather spend his time in the garden getting his hands dirty, literally, and does that as much as he can. But to dismiss weeding as a menial task is to miss the point. For a start, it requires a degree of skill, to recognise what’s a weed and what isn’t. The time and trouble taken on weeding at Dixter is enormous, and painstaking, going over every square centimetre of the garden to pick out weeds when they’re still tiny. And a weed is simply a plant in the wrong place. There are some ‘weeds’ that aren’t allowed anywhere at Dixter, such as bindweed and ground elder, because they’re so aggressive and quickly overwhelm other plants. But many of the native flower species are tolerated and even encouraged, to different degrees in different parts of the garden. Buttercups, bird’s foot trefoil, vetch, wood violets, herb robert, oxalis, and even dandelions, are all allowed to grow, in the right places.

And of course, the place where wildflowers really thrive is in the meadows. The meadows at Dixter have never been seeded, apart from the addition of yellow rattle in the early stages of development. Yellow rattle is important because it parasitises the grass, allowing wildflowers to flourish without being overwhelmed by strong-growing grasses. But the huge variety of meadow flowers in spring, including the magical abundance of orchids, have seeded themselves naturally. It’s a question of careful management, cutting the meadow down hard to the ground at the right time, and removing every bit of cut grass and plants to keep nutrient levels low. Another comment we often get is: ‘it must be so much easier now you don’t have to mow the grass all the time’. Oh no it isn’t. Maintaining the Dixter meadows from late summer into autumn requires a lot of hard work from a lot of people. Hopping onto a tractor mower every couple of weeks is a great deal easier!

The meadows at Dixter are a relatively recent development. When I first started visiting thirty years ago, most of the meadows were still mown lawns. But attitudes to horticulture are changing. By allowing more native species to become naturally established, the ‘weeds’ of past times, we can maximise biodiversity in managed gardens such as Dixter. For every ‘weed’ that’s allowed to grow, there are many more species of invertebrates that are supported, and countless thousands of microbial species. It’s part of a long, tangled food chain, from bacteria through fungi to mites, magnificent tardigrades, spiders, bees, butterflies, beetles, dragonflies, and all the birds and other vertebrates that feed on them. Diverse management of the flora of a garden can magnify biodiversity across the spectrum of all living things. Ecological surveys of Great Dixter have revealed it to be one of the most biodiverse spaces in the country. Whether you believe we’re in the depths of a mass extinction event (I think we are) or not, it’s a duty on all of us to manage our open spaces, from a country estate to a window box, with biodiversity in mind. We must all be a small part of hope. If we don’t, there will be precious little left for our children’s children’s children to enjoy.

And so I continue my Tuesday pilgrimage to Great Dixter. There is always more to do, and more to learn. But what’s so fascinating is the way so many people are devoted to the nurture and evolution of this living space, this animate, almost sentient creation, for the visitors, for biodiversity, for the greater good. And all those horticultural students that work there now will pass on through to become head gardeners in far-flung corners of the planet, having learned the skills and philosophies handed down from Fergus and from Christo, creating their own magnificent spaces long after I’ve been fed to the wind. It’s that sense of continuity, of things going on, things for the good, that’s such a fantastic feeling. I feel so privileged to be a part of it.